Introduction

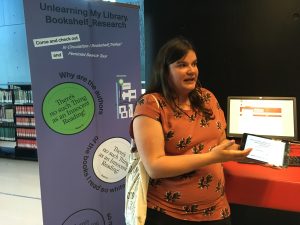

The following conversation captures a snapshot of Unlearning My Library. Feminist Search Tools1, an ongoing artistic research project exploring different ways of engaging with digital library catalogues. The project has focused on the catalogues of Utrecht University Library and the IHLIA LGBTI Heritage Collection at Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (OBA), a public library in Amsterdam. The project aims to stir conversations around the inclusion and exclusion mechanisms inherent to current Western knowledge economies. It is part of a long-term collaboration between two collectives: Read-in and Hackers & Designers. Participants in this conversation are Read-in (Sven Engels, Annette Krauss, Laura Pardo), Hackers & Designers (André Fincato, Anja Groten), and Ola Hassanain. Shortly after this conversation took place, Aggeliki Diakrousi and Alice Strete joined the collaboration.

The conversation dives into the potentials, fallacies, and desires around the project Unlearning My Library. Feminist Search Tools, which functions as a conversation piece to address questions around digital interfaces, and violence enacted through knowledge hierarchies. Participants discuss material conditions, how they are implicated, and the messiness of collaborating in a project like this.

1 Using the term Feminist Search Tools is based on Read-in’s commitment to and understanding of feminism as intersectional. The Let’s do Diversity Report of the University of Amsterdam Diversity Commission eloquently summarizes what intersectionality is about, by introducing it as “a perspective that allows us to see how various forms of discrimination cannot be seen as separate, but need to be understood in relation to each other. Being a woman influences how someone experiences being white; being LGBT and from a working-class background means one encounters different situations than a white middle-class gay man. Practicing intersectionality means that we avoid the tendency to separate the axes of difference that shape society, institutions and ourselves.” (p.10)

Unlearning My Library: The colonial project of education

Annette: Sven and I would like to start this conversation by exchanging on our different motivations to work on Feminist Search Tools. What are the different trajectories that have led the people around this table to come together to collaborate on this project?

Anja: When I think back to my first encounter with the project, it was a meet-up we organized with Hackers & Designers (H&D)2, for which we had invited both Read-in3 and Bibliotecha4. The reason for us to come together came from the question of how to approach digital libraries and digital library catalogues, how to make them accessible and searchable, which also had a copyright component. This correlated with the new Read-in practice at the time called Bookshelf Research.5 I was aware that Read-in also was interested in looking into possible ways to approach their search within larger libraries. With the small understanding I had at the time of the possibilities of searching digital library catalogues, I was interested in how Read-in’s feminist approach to looking at libraries could be applied to computational search mechanisms: How can we rethink programmatic ways of sharing and distributing knowledge?

Laura: I still remember how in one of our early Read-in sessions, we were discussing the authors, publishers, and contents of the books we have on our bookshelves at home. We started going through Annette’s bookshelves and from there we tried creating statistical breakdowns of the books she had. For instance, we looked at how many female and how many male Western authors she had. I could really connect to that. It made me think of my experience in school in Bogota. We had this subject called Spanish literature. So, you would assume for Spanish literature, you would read the big names of Latin American literature. But no, this was not the case. We had to read European male authors; we read them translated into Spanish.

We spent all this time looking to the North and to Europeans and we were hardly looking at ourselves. I only remember one single year in high school when we actually read Colombian authors. While you are still in school, you just go along with it and internalize it. I think it was only in art school that, for the first time, I was paying attention to which things we read. And again, I only encountered literature by Europeans or North Americans. You are trying to use this knowledge to understand your own practice but there was this disconnect: Why would that be helpful for me?

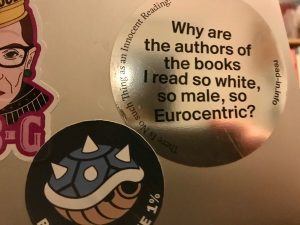

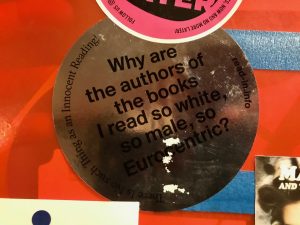

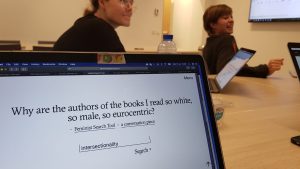

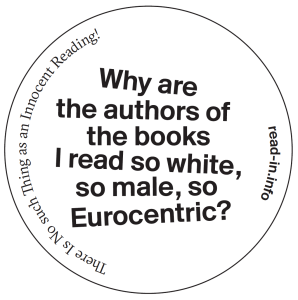

So I connect to this question – “Why are the authors I read so white, so male, so Eurocentric?” – on various levels. I grew up as if I was being read through the eyes of somebody else. And this somebody has been mostly white, male, and Eurocentric.

Annette: This question has followed us for quite a while and on many different levels. It points to the cruel dominance of the colonial and patriarchal conditions we are still living in today. For me, it is a reminder of my own implicated-ness in sustaining this imbalance, because these books literally surround me, inform my views on the world, and get reenacted in bibliographies and referencing practices. This dominance shapes the way I’m encountering the world I am a part of. The Bookshelf Research is a way to study this dominance and explore ways to intervene in it.

We experienced quite an intensification when we decided to look into the catalogue of Utrecht University Library. We tried to juxtapose our analogue ways of doing with a digital approach towards data. In my understanding, university libraries play and perform a major representative role in Western knowledge systems and economies. My motivation, as impossible as it seems, stems from the desire to approach and intervene in the injustices that come along with this dominance, and from the desire to unlearn this – my – library.

Sven: It’s super interesting to hear how you all place the different starting points of the project. For me, this leads me back to our project at the teachers’ library6 in Wiesbaden as this was my first entry point to Read-in. It quite quickly became apparent that there hasn’t been much of a change in the literature that is read in high schools between when Annette and I attended, although there is a generation between us. For me, this was a clear example of how a canon is sustained by only allowing one narrative to exist. In some ways that also made me think of what you were sharing earlier too, Laura, although through the lens of my own positionality of being white and German. I did not question back then that, of course, all the literature we were reading was by white male German authors, because that felt so much like the context I was embedded in. I find it difficult that it’s still the material they feed people today because I am more aware now of the epistemic violence that’s reinstated. For me, when we moved on to Utrecht University Library, that was somehow a logical continuation of the project we had done before, because we still dealt with an educational context, and we were still attempting to lay bare and look for possibilities of intervention in the Western knowledge economies we are embedded in.

Annette: This reminds me of discussions that we encountered a few times when Read-in presented Bookshelf Research. People, often white, would inquire why there would be a problem with reading German authors in school since we were in Germany. They had difficulties understanding how this would be different from your desire, Laura, to have read Colombian or Latin-American authors back in school or university. But isn’t the difference that those white German authors were part of the bigger modern and imperial project?

I think German authors are not only read because they are part of a specific German cultural heritage or national project, but because they are a crucial part of the bigger modern project, the European civilizing mission that has expanded itself through colonization. But in school the colonial part is hidden away. These German authors are presented and read as foundational fathers of Germany and Europe. But what is not made explicit is that in fact they are considered “foundational” for legitimizing a Europe that has aggressively expanded itself into the world and oppressed people in systemic ways. The practices of hiding away or hiding in plain sight are part of this European legacy. They are passed on over generations, often in the form of tacit knowledge. They take the form of canons but also educational practices. Contrary to what we were taught to believe, Europe as we know it today didn’t only emerge though a history of the modern project located in Europe but also through a history of colonization overseas. This means that the wealth of Europe stems from what we know as the modern/colonial project. The colonial part is very often not taken into account but is felt, as Laura’s example shows, by those that have been colonized.

Ola: I always ask myself when we try to interrogate or inquire about these structures that seem to dominate our knowledge generation processes, do we interrogate it in order to become part of it? And how do we prevent ourselves from creating the same patterns, and identify if we are represented in them once they are created? Is it a question of wanting to be part of it or a question of coming up with something that functions separately? I always ask myself when something wants to resist something, on what political markers are we basing this “resisting”? Are we making space so we can still be part of what’s going on right now? Or, do we refuse what is going on now and propose an alternative? And how can that can be sustained in spite of what is going on?

This is kind of a comment and a question: Would we like to see representation in these knowledge patterns, or would we rather look into how to generate knowledge patterns that are different and are potential alternatives to what we have now?

Annette: Is it an either-or?

Ola: Well I wouldn’t say either-or, but I would definitely say that to me one of them has a bigger weight. Because if labour is required to embed and represent things into a system that is already flawed, then it becomes quite questionable. It’s actually just the order of both propositions. It seems to me that both should be addressed, but one has to come before the other in my logic.

For me, refusal is an underlying theme of my labour. I ask myself, Is it going to be something almost integrating, and thus coercive, or is it reformist? I think this is important because it really does orient your labour and clarifies certain things, so that as you’re working, you’re not hitting obstacles or having a dilemma with, Why am I doing this? If we can imagine a wheel, I always wonder if it’s like a stone that you stick in the wheel and then things have to sort of just be? Someone needs to oil it up and take out the stone and that’s a kind of effect that I would assume goes beyond the finishing date of these types of inquiries. And of course, there’s the integration of knowledge, where you want to embed certain notions in already-existing systems that we know are failing the majority. And then there is the notion of reform and the notion of refusal. How can we set up things that would allow for us to refuse all the time, but still not fall apart?

What I am saying might be a bit conceptual, but these questions are important when trying to set up a project. We need to make the whys clear from the beginning, so that it gives us a channel, and then whenever we try to reflect, we don’t fall apart and have questions start to branch out. So it keeps going even when you hit a point where you just wonder, Why do we do this? It just helps for people to have it clear from the get-go.

2 https://hackersanddesigners.nl/

4 Bibliotecha is an open-source framework for locally distributing digital publications. https://bibliotecha.info/

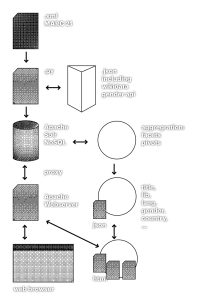

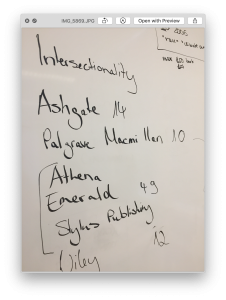

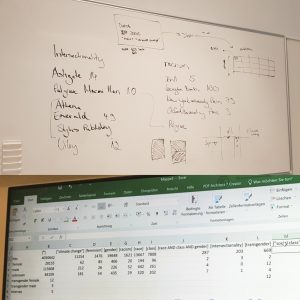

5 Bookshelf Research is a Read-in practice that experiments with counting books in specific public or private libraries according to categories such as gender, race, nationality, materiality, etc., which results in a statistical breakdown of inclusions and omissions. It also includes a huge discussion of problematizing the act of assigning categories, labels, and identifying authors.

6 The teachers’ library in Wiesbaden consisted of stacks of books (one copy for each pupil) containing mandatory literature for pupils in the high school literature class and other subjects. It’s called “teachers’ library” because teachers have easy and cheap access to these piles of books to use during their classes.

Why do we work together on Feminist Search Tools?

Sven: André, would you like to add a bit about what your motivation has been for the project?

For me, it’s interesting to not only share our reflections about why we work on this project but also why we all chose to work together. For example, for me this has been a very difficult and confronting question, especially thinking about the way we formed as a group. I think it would be interesting if we could all speak a bit more to it, and also share our feelings, possible tensions within the project, and how this has been influencing our work.

André: I think something I have never dared to ask was how it felt for you to ask “the white guy” to join the project…also being the programmer and by that holding quite some power.

I mean, I don’t feel like I’m doing this project wrong, because I’ve been doing feminist readings from my Bachelor’s in Italy – all this 1970s stuff. So, I feel like I am familiar with the project’s topic just enough. That’s why I said yes.

Maybe my interest comes from being in the position where I embody both elements. Being “the white guy” and “the programmer” but also standing behind the project. Maybe that was the underlying tension that I was feeling in the beginning. I was imagining that at some point in the exchange maybe you would ask, What’s up with you? Why do you want to participate? Do you only want to join for one part of the project? Really, why do you want to be part of this? Are you aware of what you are doing? Basically, like that.

Annette: Have you ever thought about bringing this up yourself?For me, this has always been there – exactly these questions.

Anja: Yes, but maybe we never made it explicit, which is interesting. Reflecting on the process, what I’ve been struggling with is this implicitness of positions within the collaboration – the informality of the way we work together, and the lack of structure at times. Sometimes I enjoyed the structurelessness, working without a utilitarian approach, which is uncommon in the field of technology design. At other times it also made it quite difficult to continue. There were moments when I felt conversations had to be repeated a lot, for example the question about the different roles and intentions. We’ve had conversations about it in a conceptual way. But I’ve also asked myself a lot, Why is it then that I feel I shouldn’t be designing anything while being the designer of the group? Why did we choose to work together?

It’s maybe also exactly that challenge of working within an unclear structure, with blurring boundaries between roles within the group, that made me stay with the project.

And I think our roles were also implied from the beginning. Hackers & Designers are the ones providing more of the technical part of the project or the knowledge about it. But there’s a contradiction there as well because I feel we’ve always been circling around the question, What are we actually making? But then we’re having conversations about what making actually means and there are totally different understandings of that. We tried to question these implied roles and not fall back into the habits of what I usually would do in the role of designer. It is so challenging to break these habits.

Sven: For me, for instance, the fact that we chose to collaborate seemed like a “natural” continuation of a history I haven’t been part of directly. I knew that there had been collaborations between Hackers & Designers and Read-in before, and I didn’t question that we would choose to collaborate again. But, when I had to explain to somebody else why this collaboration had come about and why, given the context we were in, we didn’t choose to work more with people of different ethnic backgrounds, races, or genders, I became very aware of how sometimes certain connections can come to seem “natural” so they are not questioned anymore and how this also informs the project. Suddenly there was an urgency for me to critically reflect on who we are as a group in terms of our different intersections and whether, as the group we were, it would be possible for us to continue this project. And what it would mean for us to do this and in what direction we would need to go.

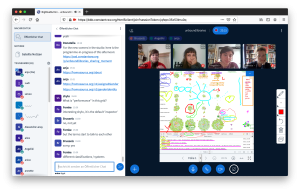

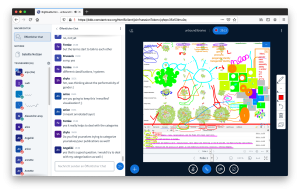

Anja: Yes, you brought up the question of how to be more inclusive as a group and the importance of including more perspectives in the project. But I also remember it took a while to come up with a solution for how to offer someone an entrance into a project so that it’s also interesting for them. We’ve met a lot of interesting people, but we didn’t want to just impose our ideas onto them, because they have their own projects and initiatives going on. Take for example last week’s workshop7 – that worked very well. This very open question of finding feminist search strategies allowed more people to engage with us in questions we have without assuming too much.

Maybe it sounds a bit simplistic to say that we failed at finding someone. I think it’s a matter of investment: the time, effort, and resources to actually commit to one another in a collaborative structure, and also to be open to possibly disregard our plans and take another route.

I was also wary about asking people into the project, because I know I would ask a lot of them. André and me, we’ve worked together for a longer time, so I could just tell you, André, what you were getting into. And I felt like I could count on you to tell me when it’s enough. I think this project has been emotionally demanding at times. And you have to deal with staying without knowing when it’s going to really end.

Annette: What you both say speaks to how to deal with the messiness in self-organized, economically precarious collaborations, and not be overwhelmed by it. And I don’t mean messiness in a negative sense. Again and again, we need to find ways to reflect on our biases that also have naturalized themselves into our group constellation.

7 The workshop “Repository of Feminist Search Strategies” took place on 08.02.2020 and was hosted by Read-in and Hackers & Designers, with Angeliki Diakrousi and Alice Strete. It focused on feminist strategies for searching in library catalogues and digital archives.

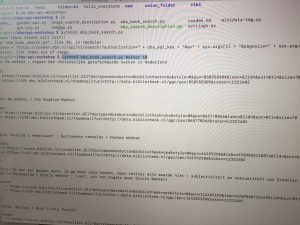

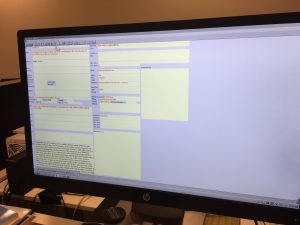

Searching as a way of learning by doing

Sven: André, when you were reflecting on being the programmer, I wonder if it even had less to do with your gender, and more that we were not really able to follow you in what you were doing due to a lack of knowledge in programming. This made it really difficult for us to access and actually understand your work. Annette brought this up many times. Read-in practices are usually based on “learning by doing” – trying things out to know where to continue. Now that we cannot do that with the technical part, and are dependent on someone mediating this step for us, it really cuts off a crucial practice of ours.

Laura: I think that’s why I have been struggling with this project. I enjoy the discussions a lot but I’m the kind of person that works by trying things out. Only by doing can I put my ideas into something. This division for me has been really hard and I have been struggling with that.

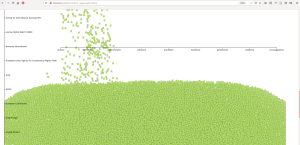

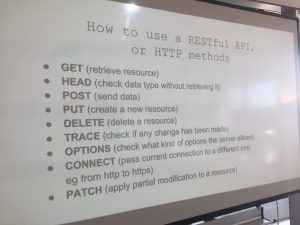

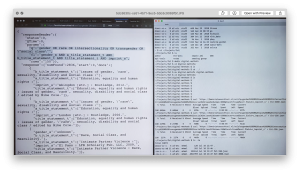

Sven: It’s also interesting to me how it did still work back then with the Utrecht University Library. It might be because the standard MARC 218 that they use still works with descriptions, which offered us an entry point to their dataset. And the expertise of the library staff has been invaluable in making sense of what those fields entail and how they’re used within their catalogue. Basically, what they offered was a translation step between the more digital realm and something that still felt approachable for me. Now it feels like putting a query into a black box that gives me something that I don’t know what it does. That makes it really hard for me.

Anja: Or, we are incapable of making a query without digging. And that’s why it’s just not happening.

Annette: Well, I’d say we have a hunch, and we trust that the process of searching will lead us somewhere. But now we are deprived of the process of searching.

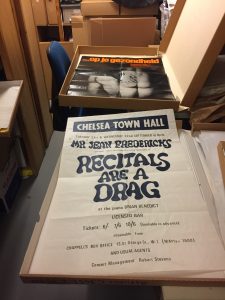

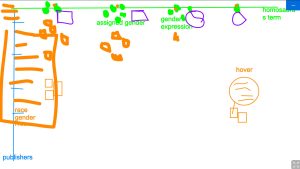

Laura: It reminds me, though quite differently, how we got introduced into work around thesauri as a form of self-empowerment. Atria Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History9 and IHLIA LGBTI Heritage Collection10 are both organizations that don’t trust the mainstream way of searching and have offered additional tools – namely thesauri – to the communities or people that use their archives.

8 MARC 21 Format for Bibliographic Data is a set of digital formats (machine readable catalogue standards) for the description of items catalogued by libraries. https://www.loc.gov/marc/bibliographic/

9 Atria Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History, based in Amsterdam, collects, manages, and shares the heritage of women. https://institute-genderequality.org/about-atria/

10 IHLIA LGBTI Heritage Collection, is an international archive and documentation center on gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and intersex history and culture. Based at Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (OBA), a public library in Amsterdam. https://www.ihlia.nl/?lang=en

Understanding one’s own tools

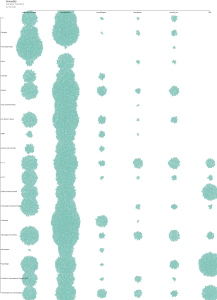

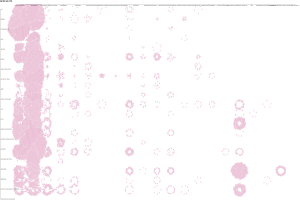

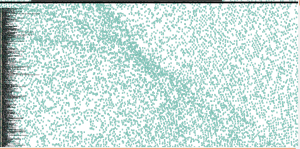

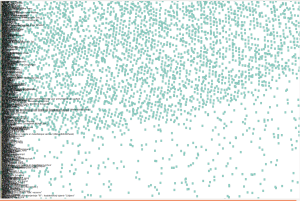

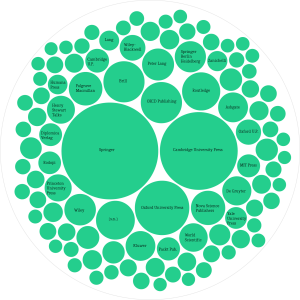

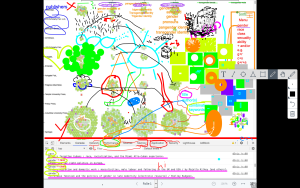

Anja: But then, at the Digital Methods Initiative Summer School,11 it helped us to work with data analysts who can work with big data and know how to query. All of a sudden, we had a visualization. The question, of course, is if that’s what we want?

Sven: I still find it a bit funny that you are so excited about the visualization tool Anja, since you were the one at the beginning of this project who was cautioning us not to expect too much, or like you put it “magic,” from the visualization. You said, the visualization will only give you what you’re asking for, which really stayed with me. And yet, we get the visualization and everybody gets excited.

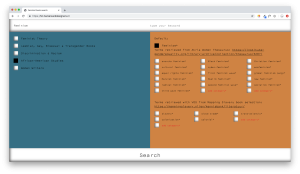

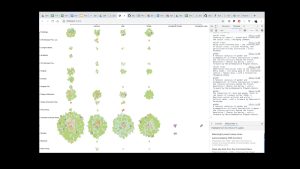

Annette: I agree that we should not project too much on visualizations. But for me the visualization tool has finally been the moment that allowed us to investigate our own tool, the first stage or prototype of the Feminist Search Tools.

Anja: The big difference for me with the visualization tool is that we can look at the books and not only at records. The books were always so important for the Bookshelf Research. Now with the visualization you can click on a square that represents the actual book and see more information about the book. This was not possible before. It was just numbers and records of the cataloguing system, which was an abstract idea and difficult to relate to, for me. Being able to check back and see some of the flaws of our initial tool was a super important moment for me. So maybe I underestimated, at the beginning, the power of visualization.

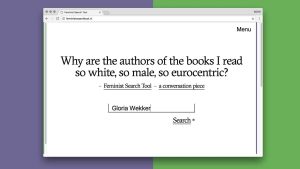

Laura: In terms of interface, that’s something that we have been struggling with from the beginning. For example, we were still using that search bar that is used very widely. It makes me wonder what it would bring us to move away from the idea of a straightforward interface?

Ola: Also, there is more to say about projects that are displaying something that could be considered alternative. For example, I did have an issue with the term “tool” as a research tool. I am still wondering, what makes this tool different from the actual catalogue tool for library users? Because the pool of knowledge is the same.

Anja: I totally see what you’re saying Ola, that we need to think about search differently. If it’s just the same stuff that you are searching, you will not find different books. There was one moment of excitement that I think many of us had. It was the “red link” concept that provided a different entry point beyond the hermetic search bar; something that is used a lot in Wikipedia pages for pages that do not exist yet. This way you can acknowledge that things are missing. So yes, maybe the pool of knowledge is the same, but it’s a more proactive and maybe even a generous way of saying that there is a book or search term that should be added.

Annette: I’m still eager to continue working in this project because of this question of what a feminist search could be. How does a feminist search move? I mean, when you search you take a certain direction, you put emphasis on certain things and not on others. Although I very much agree with Ola that we live in a flawed system, I would not want to call it total, or all-encompassing. But even if it were, I wouldn’t stop searching for cracks that might start breaking the system. I believe how to search is crucial, and we have a hunch that a feminist way could lead us somewhere.

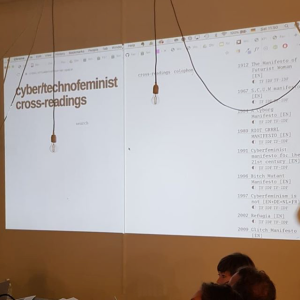

Anja: I had an interesting conversation about the Feminist Search Tools with Femke Snelting and Michael Murtaugh.12 They referred to the Feminist Server Summit,13 – a gathering of people rethinking technical infrastructures from a feminist perspective. What I found so interesting about that conversation and also a bit relieving, was the realization that a feminist search tool doesn’t have to be an actual alternative – a functioning tool. We could also take this digital object as an occasion to think through some of these systems that we rely on. It’s quite clear that we won’t be able to offer a library a better search tool; it’s more to poke and challenge ourselves. When things are not working in a tool, I get quite frustrated and I’m confronted with my own user and maker behaviours. So yes, I like the idea of not using this tool to pressure ourselves to make something “better,” but more to look at what problems we run into. To be confronted with the question, What gives me and us the legitimation to work on this? This question comes back into my mind and makes me insecure too.

Annette: I agree, Anja. Whenever we manage to take our non-functioning digital tool as an occasion to study together – as we did in the feminist strategies workshop, or in the workshop with Atria, and hopefully soon with IHLIA – then I get excited. As we say on the website, it’s a conversation piece, or a piece for studying together.

Anja: Yes, and it also says somewhere on our website, that the Feminist Search Tools is an awareness raising tool, but I prefer indeed to refer to the tool as a study object, because it challenges the expectations of an audience. For whom are we making this? That question came up a lot as well. The idea of the study object is tapping into the idea of practice. It’s about how to approach questions like these together, documenting and sharing the attempts, rather than building a tool that everyone can use.

11 Digital Methods Institute Summer School is a summer intensive program for developing “research techniques for studying societal conditions and cultural change with the Internet.” https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/DmiSummerSchool

12 https://constantvzw.org/site/

13 https://areyoubeingserved.constantvzw.org/Summit.xhtml https://gendersec.tacticaltech.org/wiki/index.php/Servers:_From_autonomous_servers_to_feminist_servers

Diverse economies and other material conditions

Sven: Let’s think now about the material conditions of the project. This might include the different moments of funding and how they shaped the project, as well as how we gave the project form.

Annette: Maybe let’s also include the diverse economies that are present within such a project and in our group. For example, how do the different people involved make sure they have time to work on the project, economically? I’ve encountered and experienced these multi-layered economies a lot in self-organized frameworks – to make a barely or only partly funded project possible.

Ola: I’m wondering what you had in mind with this question, Sven?

Sven: I think for me, one moment definitely comes to mind that shows quite clearly how funding has shaped this project – how OBA, the public library in Amsterdam, suddenly came into the picture as a project partner even though our focus at the time mostly lay with university libraries. I remember we had chosen OBA as a project partner because it could help us prove that we would have a broader reach with the project. But trying to make this step, shifting context from the university to the public library, gave us quite some trouble. I find it interesting but also confronting to see how funding opportunities have informed the direction we took with the project, and to imagine where the project would have gone otherwise.

Anja: Talking of funding, Feminist Search Tools started as a commissioned project, right? Back then, there was a clear request towards us, Hackers & Designers. This also shaped the differentiation between the one who executes, the programmer, and the one who thinks about what needs to be programmed.

Annette: Yes, Read-in got approached back then by the Zero Footprint Campus art project and the Municipality of Utrecht to think of a project that would involve a collaborator within Utrecht University, in particular Utrecht Science Park. We took the opportunity to approach Utrecht University Library, because within Read-in we had already discussed the possibility of trying out ways to do the analogue Bookshelf Research digitally. The available funding made this vague idea and desire suddenly become more tangible.

Laura: We also should not forget that although the different stages of the project had certain fundings, in the end it is primarily built of unpaid labor, or at least a hybrid of unpaid and paid labour. This precarity also informs how we work together I think.

Take Read-in as an example: the way our collective is structured is that it has always been a practice alongside which we all sustain ourselves from other sources, and certainly not from Read-in activities or projects. In terms of thinking about a self-organized collective, Read-in is economically built on a very precarious endeavor.

Sven: For sure! I think this also becomes apparent when we look at the example of Anja and Annette not being directly funded by the project because the research is connected to their PhD and postdoc.

Annette: This is also a good example for what I meant earlier by diverse economies. In my case, my participation in Feminist Search Tools is possible through our bigger Read-in umbrella Unlearning My Library, which is partially linked to another funded research project related to my postdoc. These entanglements are not always easy and certainly also co-shape what we are doing.

Anja: In my first PhD proposal Feminist Search Tools was an important case study. It played out a bit differently, but the project, especially its process, is still really important. It makes me reflect on designers’ working conditions, relationships, and how to work collectively.

Laura: Something that was really striking for me was when we had the conversation about redistributing the money that we had initially allocated for each one of our tasks. I remember the first meeting about this amongst Read-in. It felt at that time like the only way to bring in more people. We’ve always had the desire to bring in more people but then, you said it before, you feel embarrassed, because we cannot offer so much in exchange. And knowing that our process is so loose and messy, it makes it even weirder to ask someone to collaborate. I was also wondering, Anja and André, how did you feel in that moment when we talked about the redistribution of the budget?

Anja: We were thinking of asking Ola if she would be interested in joining. We would look together at the budget and see if we can secure some for an additional person.

André: Well, it was last year…I did a big chunk of programming work in the first year and I got paid an amount. Then last year it made sense to reach out to more people to join and move parts of the budget. I was happy because I wasn’t sure how to be useful, how to bring the project forward at that time. So, I thought, let’s move this budget to somebody else.

Anja: But the good thing is that Hackers & Designers have our own economy. So when André came to The Netherlands, we could secure some budget for the travel costs at least. And with Andre’s involvement, on behalf of Hackers & Designers, in the Digital Publishing Toolkit research project at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, another income was secured. Combining several involvements in different projects is certainly something very common in the cultural field.

Annette: It’s quite valuable to disentangle these diverse economies from time to time. Needing these different involvements in order to generate an income also means having to spread one’s focus over quite different projects; very often the workload increases and it becomes a question of rhythm too. How to juggle the different temporalities and workloads of projects?

Sven: I also remember that we were struggling with the fact that we had given the programmer quite a big portion of the budget in comparison to all the other work that had been done. For the second phase of the project, we discussed how we could value our own work and the programming work equally, in terms of the money that we would receive for our hours. We had quite some conversations amongst ourselves of how we also wanted to counter a value system for our work that our current economic system suggests to us.

Anja: And this distinction of the programmer as the one who is not researching is also problematic.

Sven: Ola, would you mind speaking a bit to how you feel about coming in at a later stage of the project, how you see your role in the project?

Ola: Annette and I discussed possible involvements briefly before. Because at that time you had already produced something and I thought I could come and go with a role of asking questions if people need me; when you guys want to converse more and reflect more, then I can come in. So, we discussed the possibility of coming in and out. So far these discussions were around how I could contribute, but also what people would like from me in a concrete manner. But also, if the group needs someone, or they want to change the scale of things, what are people proposing to do? Basically, I wanted to see how people are going to deal with this problematic structure that your project is embedded in. Can we actually be critical and also poke certain holes? But also, how do we identify certain stakes?

From a user’s perspective, libraries frustrate me every time I go to look for information, to the point that for a very long time I abandoned going to libraries, because I felt so lost when I walked into them. I always resort to going to the reception to have someone talk to me. Libraries always seem like a mini world, a place where you have world-making views, and of course they also disseminate world-making views. In this group I was concerned with the role of asking questions, because I thought I might be wanting answers to some shit that people aren’t really concerned about right now, you know?

14 Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam https://www.oba.nl

15 https://www.zerofootprintcampus.nl/en/

![[ ID ] Silver sticker with the question "Why are the authors of the books I read so white, so male, so Eurocentric?" sticking out of the bookshelf of the IHLIA Heritage Collection, Photo: Thea Sibbel](https://feministsearchtools.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Thea-Sticker-300x300.jpg)