A conversation1 amongst members of the Feminist Search Tools working group (Angeliki Diakrousi, Sven Engels, Anja Groten, Ola Hassanin, Annette Krauss, Laura Pardo, and Alice Strete)

Introduction

The Feminist Search Tools (FST)2 is an ongoing artistic research project that explores different ways of engaging with digital library catalogues. It studies the power structures that library search engines reproduce, and offers an intersectional lens to (computational) search mechanisms to inquire how marginalised voices within libraries and archives become more easily accessible and searchable.

While the initial FST study process started in the context of the Utrecht University library, it changed context and revolved at a later stage around the catalogue of IHLIA LGBTI Heritage Collection, Amsterdam.

The following is a continued conversation amongst members of the Feminist Search Tools project. The first conversation focuses on the different motivations and contexts that informed the FST project, and includes reflections on the modes of working together. This follow-up conversation zooms in on the ‘tool aspect’ of the Feminist Search Tools project, its situatedness and processual character, and the different (mis)understandings around the term “tool”.

During the ongoing collaboration, the tools have taken different shapes and forms, however have never really solidified in a way that they could easily be applied to other contexts than those they were developed in. Instead, we have attended to the tool-making or tool-imagining process, which gave space to complexification, and expanded our understanding of tools (digital and not) and their implications for specific contexts.

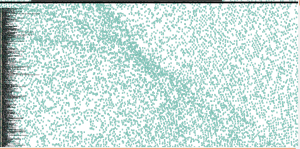

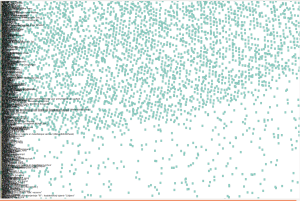

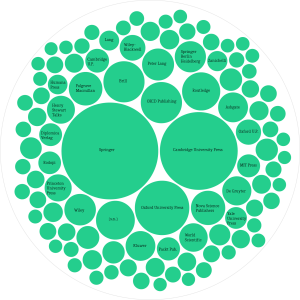

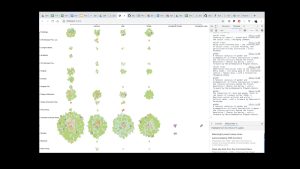

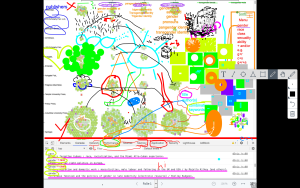

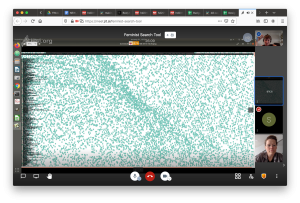

The composition of the Feminist Search Tools working group has changed throughout the project.While Sven Engels, Anja Groten, Annette Krauss and Laura Pardo initiated the early version of the FST project, Angeliki Diakrousi, Alice Strete and Ola Hassanain joined the process and problematization of the ‘visualization tool’, as it was first started during the Digital Methods Summer School in 2019. The following conversation took place after the visualization tool was presented in a public setting and a funding cycle for this iteration was completed.

Tools as “modes of address” and “digital study objects”

Anja: Considering that we had all very different encounters and experiences with the tools created throughout the project, I propose to start our conversation with an open question: What were everyone’s initial expectations towards working on a digital tool, and how have these expectations been met, or perhaps changed over time?

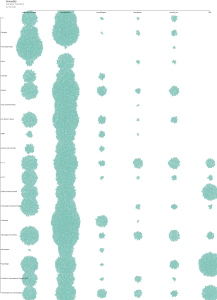

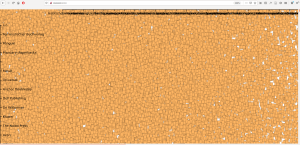

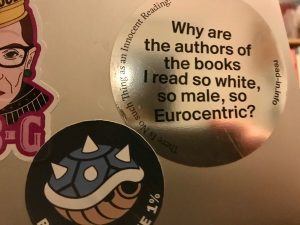

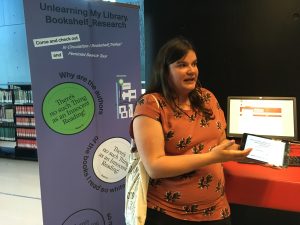

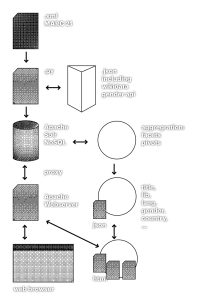

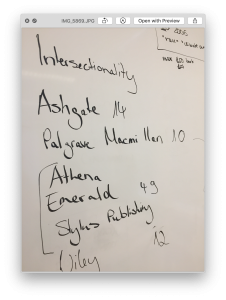

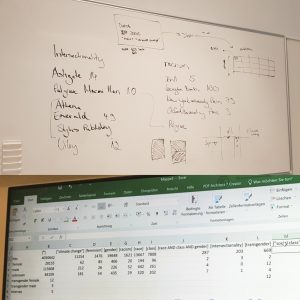

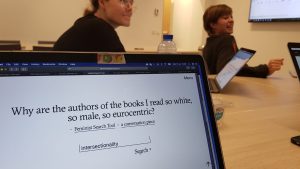

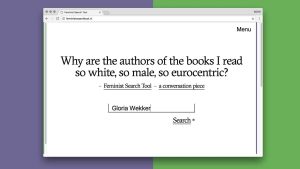

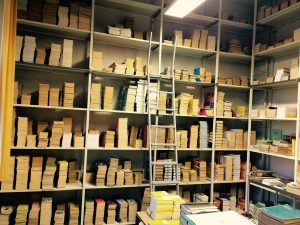

Annette: I still remember how some of us in Read-in got interested in the term ‘tool’, and more specifically a “digital tool” through the question of scale. During our previous project titled Bookshelf-Research, we physically spent quite some time in small (grass-root) libraries studying the categorizations of publications. For me, the Bookshelf-Research was actually already a tool. By literally passing every single item of the library through our hands, one after the other, we got acquainted with the library and tried to figure out the different categories, such as publishers, languages, gender of authors, materiality and contents of books. For instance we looked at the Grand Domestic Revolution Library of Casco Art Institute, which holds around 300 books. The digital dimension of the tool became more explicit, when we shifted our attention to the Utrecht University library. As the library holds three million books, a contextual counting exercise in the physical space was no longer possible in the same way. What has remained throughout is the desire to challenge the coloniality of modern knowledge production that we attempted to address in the question: “Why are the authors of the books I read so white so male so eurocentric?”

Anja: You earlier referred to the Bookshelf-Research as a tool. What do you mean by that? Do you regard “tool” as a synonym for method?

Annette: I’d rather see “tool” as a mode of address – or a set of search mechanisms, or maybe even principles. I think it has to do with my disbelief in the possibility of transferring methods from one context to another without doing much harm. A mode of address proposes something that a method has difficulties to attend to, namely situatedness and context-specificity.

Sven: I think for me at some point I had started equating tools with “digital tools” in my head. This created a disconnect for me, because I felt I wasn’t that easily able to access what those tools do.

At the same time, the notion of the tool as a “digital object” – an interface – also came with the expectation of usability of the tool. This also brings up the question of “use for what” and for “whom”? For instance, the expectation that a tool should also produce some form of result was put into question. Thinking about the tool as a digital study object creates the room to explore these and other questions and what the tool actually does.

Anja: The idea of a tool as an enhancement, that’s supposed to make our processes easier, processes that would anyways happen, that might have been also causing some confusion around the project, don’t you think? Interesting and important confusions and again also expectations.

Laura: When we started talking about tools rather than the tool, my perception and expectations changed. From the beginning, when we were talking about the FST project – for instance during our first conversation with ATRIA, we had questions like: “Is the tool going to work?” There has been indeed a certain expectation of the tool to produce a result, or a solution to a problem. The fact that we would make a digital tool made me especially scared and cautious. In my understanding of digital tools, they tend to be binary, it’s either this or the other. Everything in between gets lost.

Realizing there is not just one tool but different modes within which you can ask questions, – moving the tool to the same level as the conversations we have was a very important part of the process – to realize there is not only THE tool.

Sven: When you talk about the things that get lost do you refer to the decisions made that factor into a tool or are you referring to the conversations that are part of the tool making process that might no longer be visible?

Laura: It’s both. We always say that moments like this – our conversations are so valuable and important. When you have a product – a finished search interface for example – those conversational elements can get lost. I think it is great that we bring the conversations, pieces of audio or the images together on our project website. But when making some kind of tool you also need to come up with solutions to problems right?

Angeliki: From listening to your thoughts, I want to relate back to how scale played a role for you in the beginning. When the database becomes so big, that somehow you can’t relate to it anymore as a human. It exceeds your understanding and therefore challenges matters of trust. I also like the idea of the conversational tool because it means the tool can be scaled down and become part of the conversation and doesn’t have to give a solution to a problem. In conversation with the tool we can address issues that we otherwise don’t know how to solve. If we don’t know how to solve things, how would a tool solve them? The tool is our medium in a way. I am interested in finding more of these bridges to make the tool a conversational tool.

Annette: I have grappled with the role of scaling throughout, being attracted and appalled by it. This is what I tried to point at above with modes of address. The work of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing could be interesting here, when she refers to scaling as a rigid abstraction process. She criticizes science and modern knowledge production for their obsession around scalability. She describes scalability as the desire of changing scale – expanding a particular research or production without paying attention to the changing contexts. This has provoked many colonial violences because scalability avoids contextualization and situatedness in order to function smoothly and therefore ties in with an extractivist logic.

I believe by means of conversations we attempt to bring back context and situatedness. Conversations ground us.

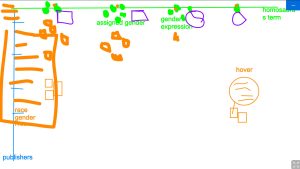

Laura: Isn’t our struggle with addressing the question of gender in our first prototype not just an example in this direction? We are working with a big database and have to find solutions to address certain questions, and by choosing a specific solution many other modes are not chosen, and we know these choices also lead to misrepresentation.

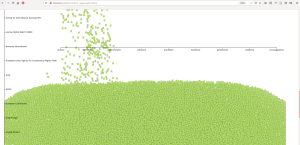

Alice: I remember, we were looking for the gender of the authors at the beginning of the project, approaching it by looking at the data set of Wiki Data. I think at that point I expected that the information would be available for us and we just need to find it, and figure out how to use it. But then I realized I have to adapt my expectations about how to extract insights from moving around the database, which was not obvious to me from the beginning.

Sven: The biggest clash in that regard for me was when we tried out the Gender API. It attributes gender on the basis of names and the frequency a name is used for a particular gender online. Not only does this lead to faulty results, but it does feel harmful using it for gender in this way when self-identification is so central to gender identification. This definitely forced us to rethink how gender could be identified in different ways and with different tools that also take self-identification into consideration.

Ola: When I joined the project, I asked questions that derived from some concern about the classifications we would be using and how the tool would filter certain searches. My concern was that the tool would take us from one way of classifying to another. When you look for ‘knowledge’ – at least from my perspective – there is a level of caution that you have to take. These general classifications are out there and while you do not adhere to them or abide by them they are there. I had a brief conversation with Annette about the tool having to change every period of time. To make a point I used an example of the Neufert architectural catalog, which has become a guideline for international standardization of estimation of distances around architectural things. If you want to design a table you have all these ranges to estimate with, – distances, heights, …. So basically, whatever comes out of architectural design goes through – or operates within a fixed framework. Anyway, my question is whether the tool building has its own space, or is it building upon the categories and classifications that the libraries are using. The interesting thing about the Neufert catalog is that it gets updated every year, or every other year. It’s pushed back into the design world, as a new edition every time, as something that is regenerating. So how does a search tool respond to something that is constantly changing?

Annette: I understood the Neufert catalog more as a standardization tool and normative rules comparable to the library classifications developed by the Library of Congress. However, you actually stress its flexibility.

Ola: The tool has to cater to that constant change. My suspicion was about whether we can have more diverse or inclusive ways of using or finding references, and books and what informs such a process basically? If we have something like the Neufert catalog already set up in the libraries, how does the tool respond to that, and how does it regenerate?

Anja: When you refer to changeability and the challenge of correcting systems of categorization, I have to think of the text by Emily Drabinski “Queering the Catalog: Queer Theory and the Politics of Correction”, which also Eva Weinmeyr’s and Lucie Kolb’s research project on “Teaching the Radical Catalog” was inspired by. Drabinski discusses practices of knowledge organization from a queer perspective and problematizes the notion that classification can ever be finally corrected. According to Drabinski there needs to be a sustained critical awareness – and ways of teaching catalogs as complex and biased texts. I remember the Unbound Library Session, organized by Constant in 2020, during which Anita and Martino, – who are self-taught librarians working at the Rietveld and Sandberg library – presented their library search tool which allowed the users of the library catalog to suggest new categories. Thus as someone searching in the library catalog one can also make suggestions for modifications of the cataloging system itself. The librarians would then review and then apply or reject the suggestions. Their idea was to organize discussions and workshops with students and teaching staff around such suggestions. It is quite exciting to think about the changeable catalog becoming dialogic in that way.

Alice: It is a big difference to use an existing search tool – into which you have less insight – as to making something from scratch so to speak that integrates conversation at every step.

I appreciate the possibility to pay attention to the decisions that are being made in the different phases of the process.

Sven: I wonder to what extent the idea to build something from scratch is even possible or desirable? It often feels that projects are trying to come up with something new and innovative, instead of acknowledging the work done before by others and embracing the practice of building on and complexifying what already exists. I feel it’s definitely also a trap we’ve been very aware of ourselves and that we attempted to focus on the latter, while making room for different perspectives and questions.

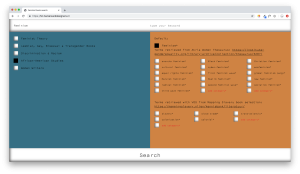

Annette: I understand Alice’s comment more in terms of a search interface as black box. And indeed, we have literally built upon existing tools like the Atria Womens Thesaurus, as well as the Homosaurus of IHLIA, and all the references that Anja mentioned. There are loads of tools, or experiments of tooling that we have struggled with, for example the first prototype, the ‘Feminist Search Assistant’, the paper prototypes, and the Visualization Tools (Digital Methods Summer School; IHLIA).

Where does the agency lie within the tool?

Laura: When it comes to user interfaces, we are so used to smooth interface designs that feel like ‘magic’, like filling in a search window in Google, for instance. You just type something and you don’t know what is happening in the backend. It just shows you the result. I was always hoping that we would do the opposite of this, or something other than that.

There is a lack of agency I experience with digital tools. With analogue tools I don’t have that feeling. I have a hammer, and I know how a hammer works. I am somehow much more frustrated as a user of digital tools. I don’t know how to break that distance with such tools. I think we were trying to close that gap but it still feels unattainable at times.

Anja: This reminds me of a subsection in our previous conversation that I wanted to speak more about. The section “Understanding one’s own tools”, and the implication of ownership over a tool. Even though often hidden, don’t our tools in a way also own us? And also, when we think about tools, for instance software – we often think about them as separate from us. There is an alleged separation between the tool builder, the tool and the tool user. I found it so interesting in our process – as much friction as it brought – it became very clear how a tool is actually not so separate from us. Every conversation also was informed by the tool and in turn shaped the tool. But also we – as a group – were shaped by it’s coming into being, – and also constantly confronted with our expectations of our tool relationship.

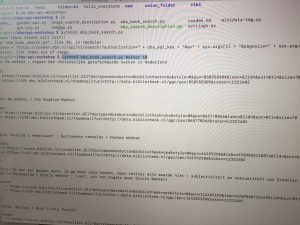

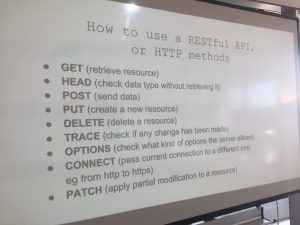

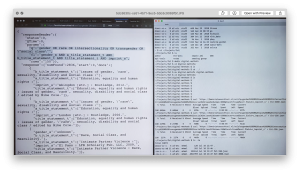

Angeliki: I wonder how the code could actually also become part of this conversation. For instance, the ways we categorized the material in the code. Thinking about the code and realizing that creating intersectional axes practically meant we had to bring everything inside the same place. Everything had to become one script.

To be able to create the different axes we connected the different terms in that script. The way we categorized the code, the file, and the scripts should be also part of that conversation. Because the code is also built on binaries and structures and is written in ways which make it difficult to complexify. It’s actually difficult to find possibilities to make a split. We are not professional software developers. We just happen to know a bit of coding. We are learning through this process. I am sure the tool can be much more innovative in the way it is structured. It also needs a deep knowledge of the initial library tool. But yeah, this was an interesting process. I would actually like to see this conversation and the learning process reflected more visibly in the tool.

Annette: Which brings us back to the ‘conversation tool’. All these conversations and encounters are so necessary because the digital tool itself makes them so invisible in a way.

Anja: But how could they become more visible? These conversations indeed became a useful ‘tool’ for our process as they offered us committed moments of collective reflection. On the project website the conversation became also quite important as a narration of the website as well as a navigation. But what happens after the conversation? The idea of releasing and handing out the digital tool seems to be still a difficult subject for us. The way we go about release is by making the process available and hyper contextualizing it. There have always been specific people, specific organizations that we engaged with – and to a certain extent we also depend on these people in moving forward. Don’t you think there is a danger of these conversations amongst us becoming self-referential? We do publish and release the tools to some extent through these conversations and through other forms of activation such as the meetups, but how do we make sure that the Feminist Search Tools in some way contribute or feed back into the communities they were inspired by?

Sven: The conversations are maybe more part of the background in the digital tool itself. If we think for instance of the website and the project itself, we try to bring them more to the foreground. It’s something to keep in mind again and again how central these questions are to the project itself.

Exploring intersectional search as a way to move beyond identity politics

Anja: In the previous conversation we clarified that we understood feminist as intersectional – “avoiding the tendency to separate the axes of difference that shape society, institutions and ourselves”

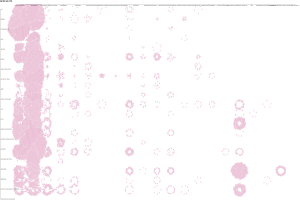

With the last iteration of the tool – we tried to literally intersect groups and axes of categorization, but at the same time also created new kinds of separations in order to make certain things legible, and others not. How are those separations, in fact feminist separations? And in what ways did the tool perhaps share our understanding of feminism?

Sven: Annette and I had a conversation with Lieke Hettinga whom we had asked for input to further explore the x-axis terms of the visualization tool related to disability due to their expertise in disability and trans studies. Hereby, Lieke had questioned to what extent – when using the clusters of gender, race, sexuality, etc. – we are just reinstating identity politics, and to what extent we are able to move beyond these categories. By looking at categories separately but also trying to find connections between them, this reminded me of the underlying tension of this project, us needing to name different categories relating to identity in our question “Why are the books I read so white, so male, so Eurocentric?, while desiring to move beyond them. These conversations and tensions have been an important part of the process but aren’t necessarily so visible in the tool as it is right now. How can we show such tensions and struggles that we come across while approaching a tool like this, and make them accessible to people engaging with the tool and have them be part of the conversation about it.

Angeliki: I am thinking about the notion of an introverted process. I think it is important to include the people this tool refers to but maybe not always so intensively and perhaps people don’t have to understand it completely. It’s good that it’s clear that when we say tool we don’t speak about a tool that gives solutions to problems. For me it’s important that people understand the conversational process, and that they should be part of it, and that they will also affect the tool.

How can a reflection of this process be opened up? How can we engage more people in this process? Maybe it’s through workshops, or small conversations or a broadcast?

To me this relates to feminist practice – that the tool is applied in different layers. Not only in how you make the actual tool but also how you communicate about it, how you do things, take care of the technical but also the social aspects.

Use value and usability

Sven: I had to think of the metaphor that Ola had brought up in our first conversation – the tool as a disruptive mechanism of: “Throwing stones into a wheel”, which nicely translates to the tool existing in power structures. But at the same time I do have to admit there is also a desire around usability of our tool, which for me stems from wanting to find queer literature. I want to be able to find that identification in the material I am looking for and I still find it very frustrating not being able to find that within mainstream media outlets or libraries. So, I think we should also not so easily do away with these hopes and desires that come with the use value of a tool. There are a lot of desires and hopes around that! I think it is also interesting to think through both: We can of course be critical about efficiency and usability of a tool. But at the same time, we need to understand where that desire is coming from – wanting the tool to function and providing something to someone engaging with it as well.

Ola: The desire to actually find something cannot be separated from the rest of the commentary we made in terms of its efficiency of the tool as you said. That’s the issue. When a tool is used, it creates issues as it is being used. The desire and everything you just said are not isolated things. I think that’s maybe not hard to imagine – but maybe hard to articulate, in terms of how we think how the functionality of the tool should be, or how it operates within the library.

Alice: Can I ask Ola, would this be an argument against usability of such a tool?

Ola: No, this is not an argument against usability but against the fact that we think it’s not. That it is something separate. To look at its usability as something that is sort of neutral and separate. We shouldn’t do that. Because that is part of the problem. It creates and perpetuates the same issue because the tool is already something that gives analytics to the bigger body of the library. And through that patterns are formed. And the interface responds to that. So, we are caught in an enclosure of this desire that is already informed by how the knowledge is institutionalized or how that knowledge is classified. So, I think there has to be awareness of that.

Angeliki: The way that I envision it, it’s not going to be a ‘beautiful’ interface that is easy going. It will show the fragments of learning that went into it.

Anja: Yes, the tool also demands a certain level of involvement, – care and commitment. It is perhaps not thought about as something that can be finished – that standing on its own, but as something that is never resolved and needs continued engagement – a practice.

Annette: For me it links back to the attitude towards the tool – towards this black box. I don’t believe that we can ever have a complete understanding of any tool. But we can strive for a certain kind of literacy that supports both a questioning attitude, and is dedicated to the quest for social justice. This might be crucial in order to address the complicities of the modern project of education that libraries are embedded in.

![[ ID ] Silver sticker with the question "Why are the authors of the books I read so white, so male, so Eurocentric?" sticking out of the bookshelf of the IHLIA Heritage Collection, Photo: Thea Sibbel](https://feministsearchtools.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Thea-Sticker-300x300.jpg)